Kinetics¶

You may recall that dynamics has two main parts: kinematics and kinetics. In kinematics, we studied motion without considering the forces causing the motion. Then, we introduced you to concepts such as mass/inertia scalars; forces; moments; and momentum functions. This builds up to the second part: kinetics.

Kinetics is the final piece of the puzzle that relates all forces acting on bodies to the resulting motion.

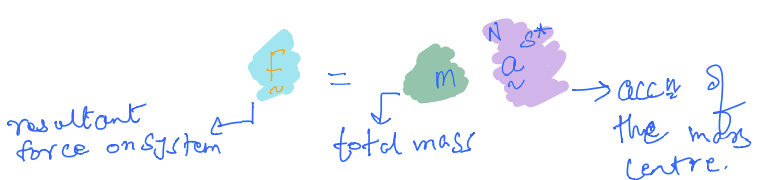

The basic relation between force (all forces on a system) and acceleration is found in Newton’s second law:

\[ \vec{F} = m\vec{a} \]

Key Concept: Inertial Frame¶

In our discussions within kinematics, we have described positions in space of objects (i.e., points and reference frames) relative to some other reference frame by means of linear and angular measurements. In many cases, we made use of reference frames that were fixed (i.e., the ground).

Newton’s laws of mechanics are valid in a frame known as inertial reference frame (or inertial frame or Newtonian frame).

Definition 1: Textbooks often define something known as a primary inertial system, which is a reference frame that is neither translating nor rotating in space. The laws of Newton are said to hold in this frame; experiments show that the laws are valid in such a frame as long as the velocities involved are negligible compared with the speed of light, which is 300 000 km/s. Consequently, for several engineering problems, the Earth can be approximated to an inertial frame in studying the motion of objects moving on it (like cars) and close to it (spacecraft in Low Earth Orbit).

Definition 2: It is also seen that Newton’s laws hold in any non-rotating reference frame that moves with a constant velocity; the time derivative of a constant velocity leads to zero acceleration. Thus, another definition emerges for an inertial frame as a frame which has zero acceleration (or is a non-accelerating reference frame).

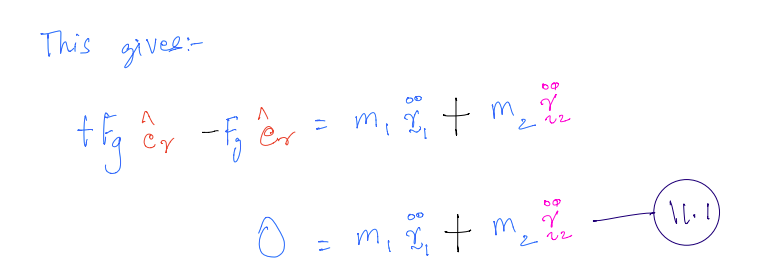

As a result of the two definitions above, you will also commonly see books define an inertial frame in a rather circuitous manner as a frame in which Newton’s second law ( handwritten equation above) is valid. Now you know why.

Equations of motion¶

Newton’s second law (as stated above) is a vector equation; indeed, they can be written as 3 scalar equations:

The set of equations are what are called Equations of Motion.

The above equations can be used to solve two types of problems:

Acceleration is known and we have to calculate the forces: Acceleration is either specified or can be determined directly from known kinematic conditions. The corresponding forces on the particle can then be directly determined from Newton’s Second Law.

Forces are known and motion needs to be determined:

Case 1: If the forces are constant, the acceleration is also constant and is easily found using the equations of motion.

Case 2: In the most general case, forces are functions of time, position, or velocity; so the above set of equations are differential equations. These are more challenging problems. Deriving these general equations with the aid of is the goal of this portion of the module.

Free body diagrams to determine forces¶

Developing equations of motion requires that you account correctly for all forces acting on any object.

The only reliable way to account for every force is to isolate the particle under consideration from all contacting and influencing bodies and replace the bodies removed by the forces they exert on the particle isolated.

Note that not all the forces are known in terms of their magnitude e.g., reaction forces (this will become clearer later); but we need to account for all forces at a qualitative level in our free-body diagram.

Types of forces to account for:

Gravitational forces:

Friction forces:

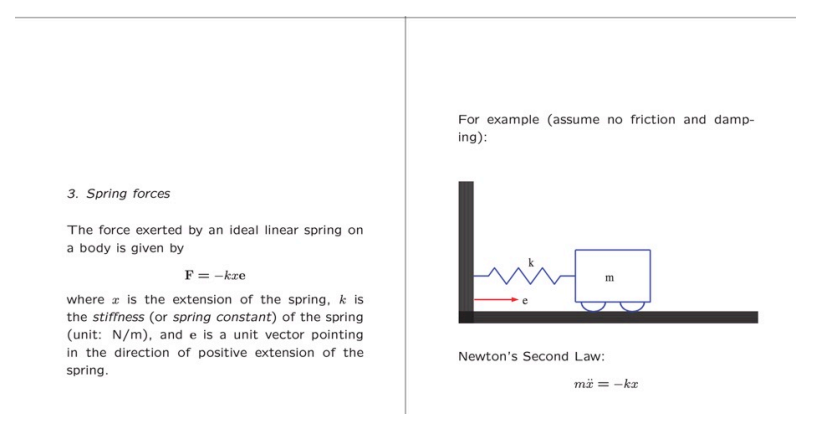

Spring forces:

Fig. 1 Spring forces¶

Types of motion¶

There are two physically distinct types of motion:

Unconstrained motion: where the moving object is free of mechanical guides and follows a path determined by its initial motion and by the forces which are applied to it from external sources. An example here is the motion of a satellite or a rocket in flight.

Constrained motion: where the moving object is partially or totally restrained by guides. Thus, in addition to external forces, there are also reaction forces that emerge in this case. An example of fully constrained motion is of a train moving along a track. The motion of a car is another example as it is constrained to move on the horizontal plane.

Kinetics of a Single Particle: Unconstrained Motion¶

For a particle \(P\), moving relative to a frame \(N\) under the influence of an external force \(F\), we have Newton’s second law:

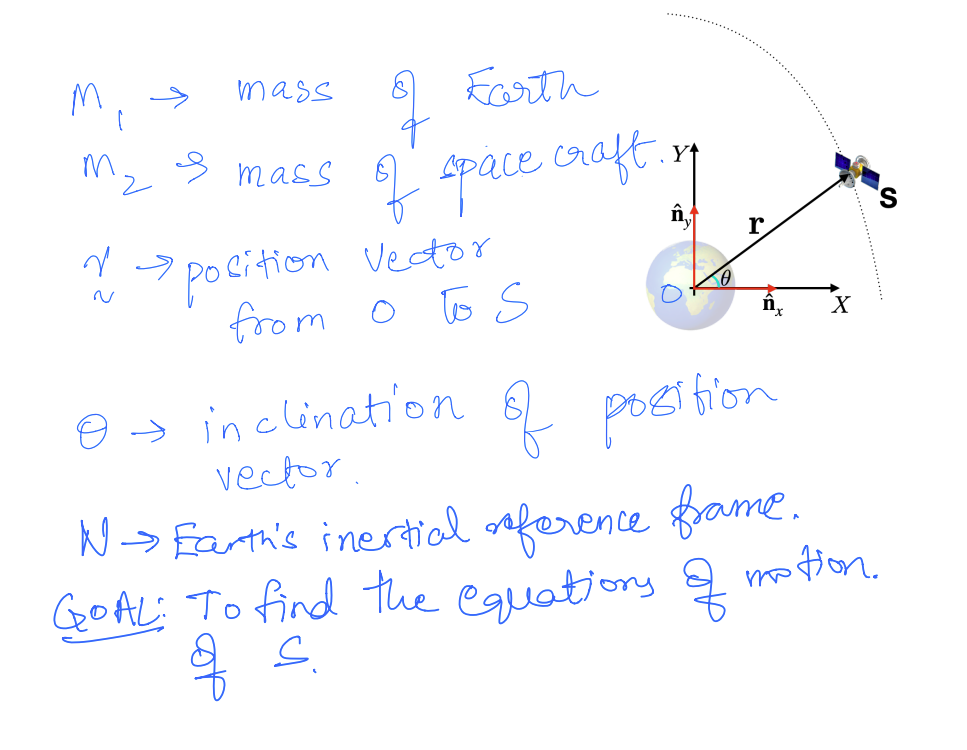

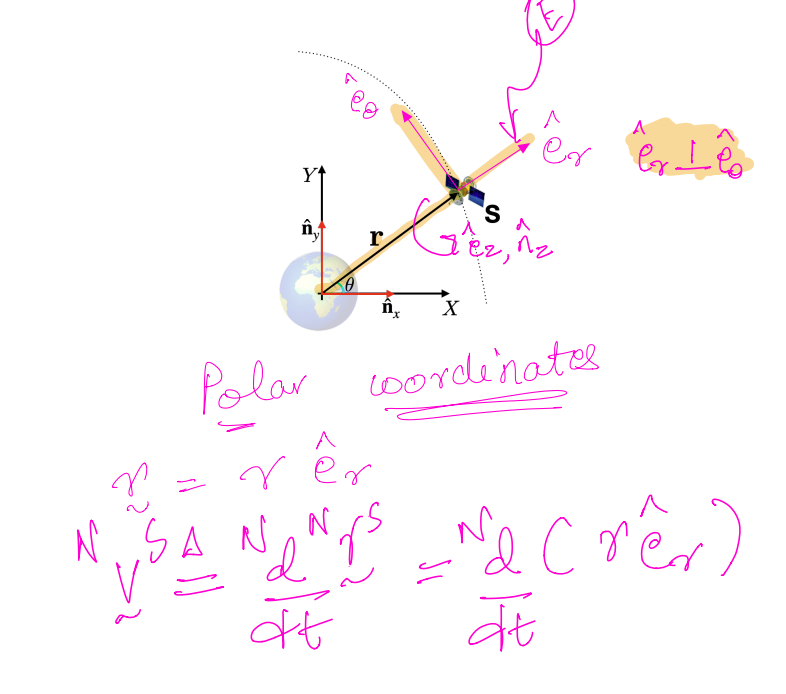

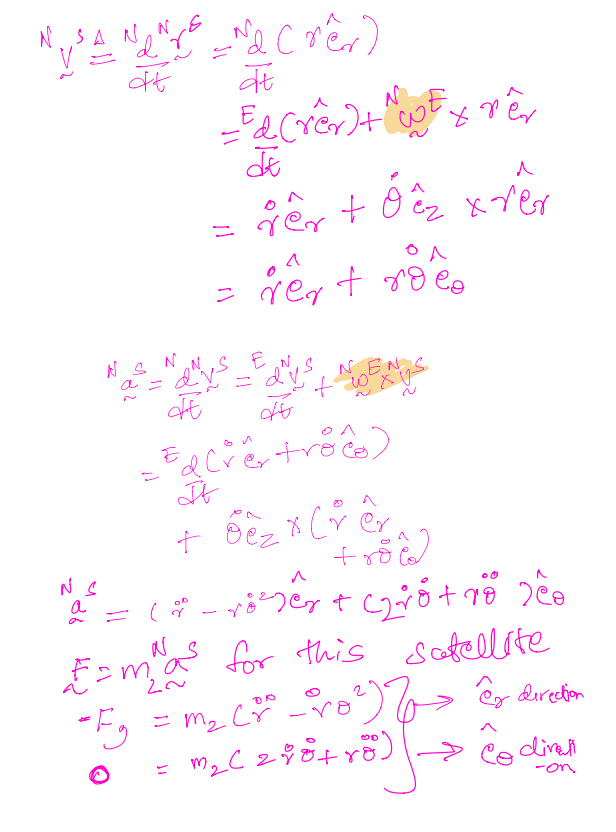

Practical example: The case of motion of a \(S\), a spacecraft, about the Earth:

Attention

GOAL: To find the equations of motion of \(S\).

Tip

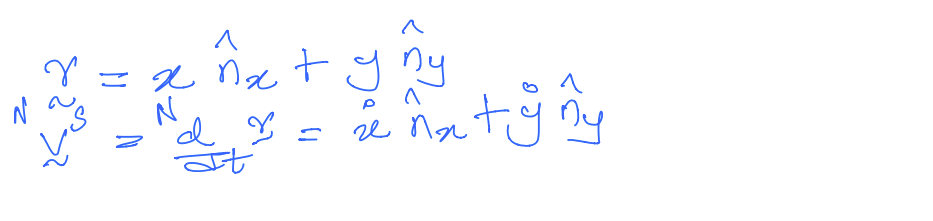

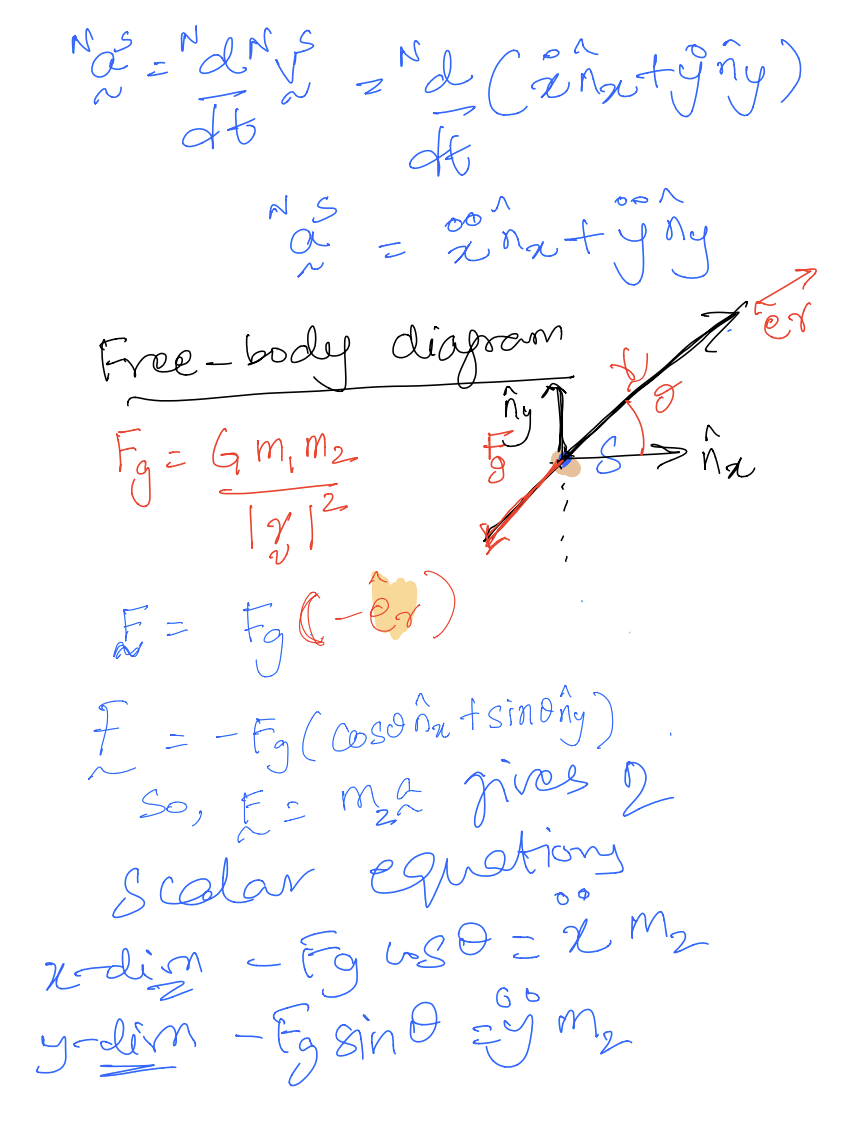

Using cartesian coordinates

Hint

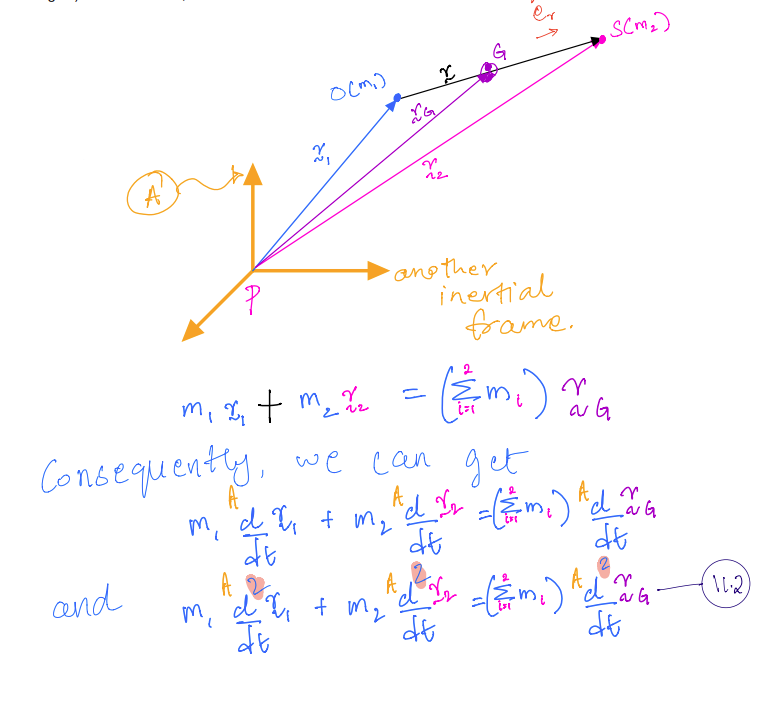

Recall that, systems of particles have a fictitious point called the mass centre; let’s call it \(G\) in this case (see figure). In this scenario, we have the definition of the mass centre as:

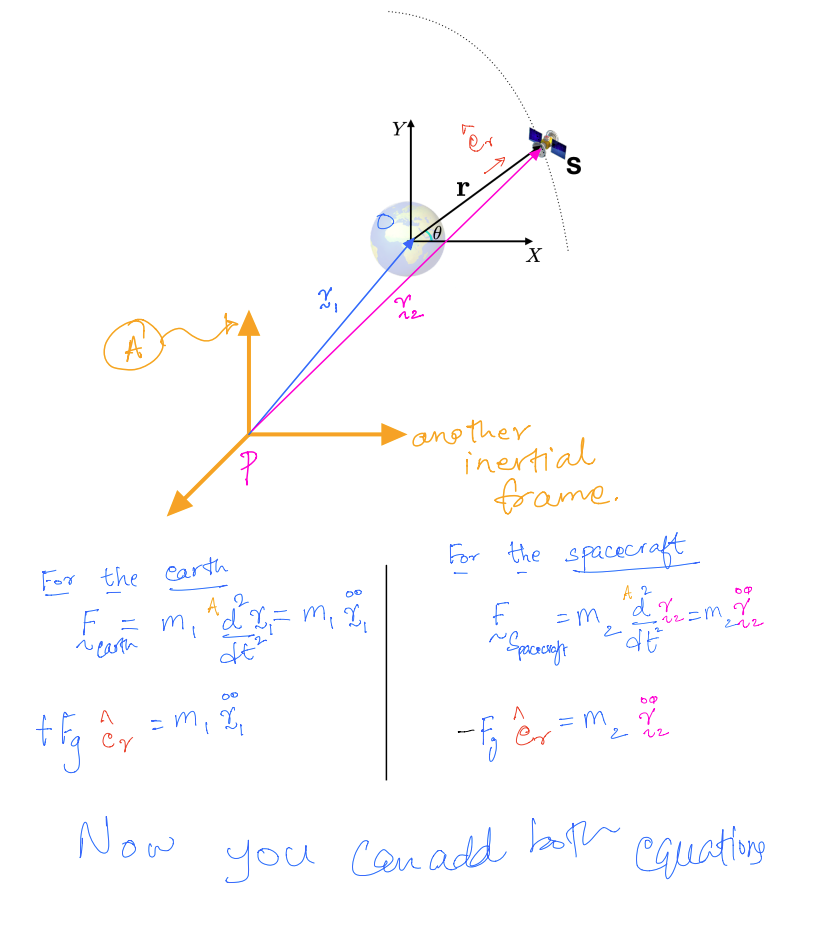

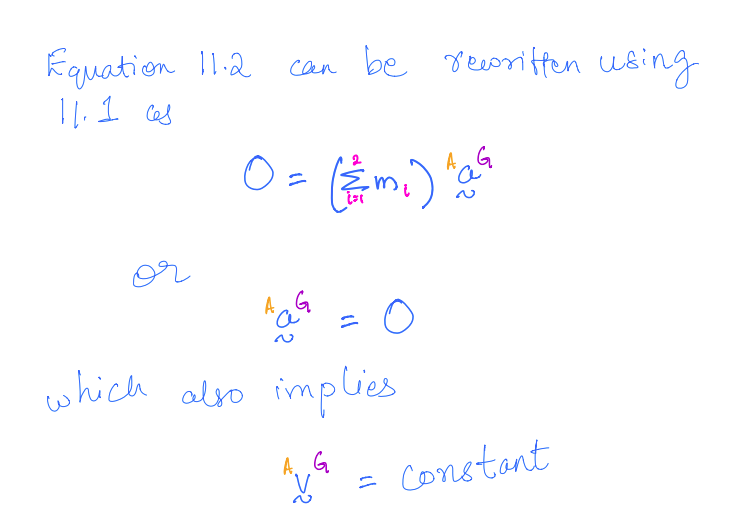

So, what we have done in this second discussion is considered the motion of a system of two particles- one particle is the spacecraft and the second particle is the Earth. What we see is that we can study the motion of each particle from an inertial frame and then combine this information to study the motion of this two-particle system from its combined mass centre, \(G\).

It turns out that this development of Newton’s second law for two-particles actually generalizes to a system comprising \(n\) particles and also to a rigid body. Let’s examine this further in the next section.

Generalized Newton’s Second Law¶

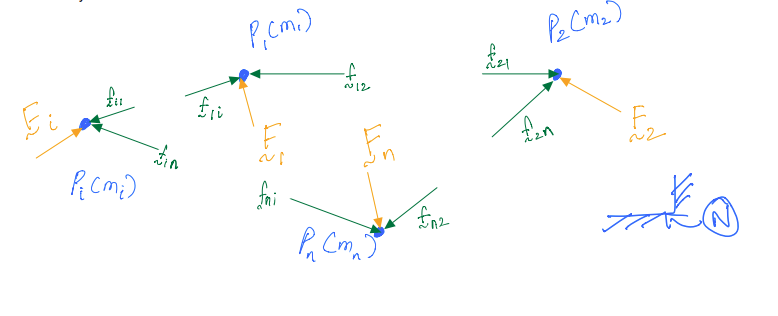

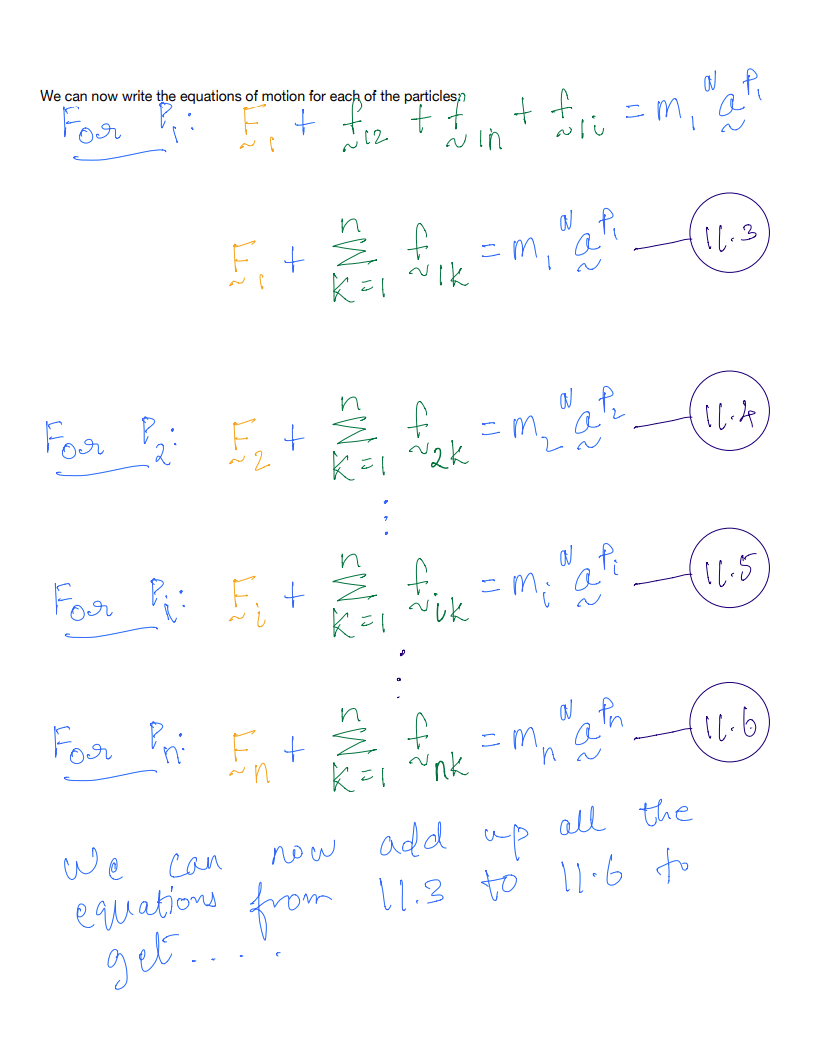

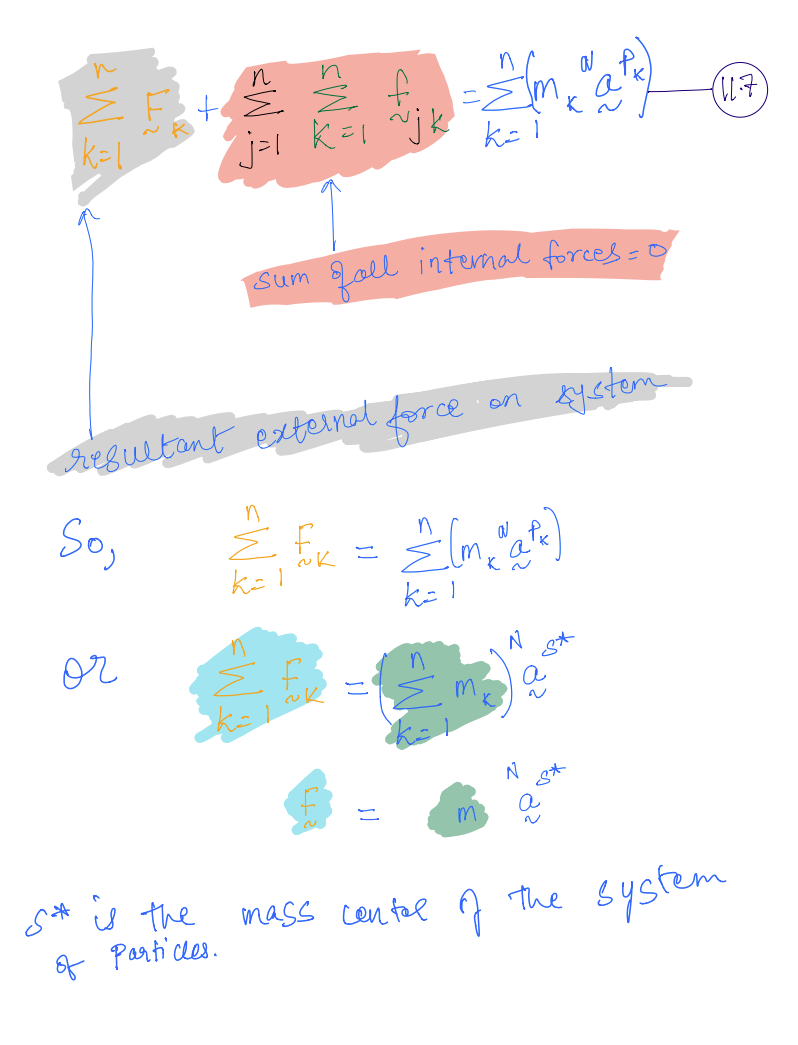

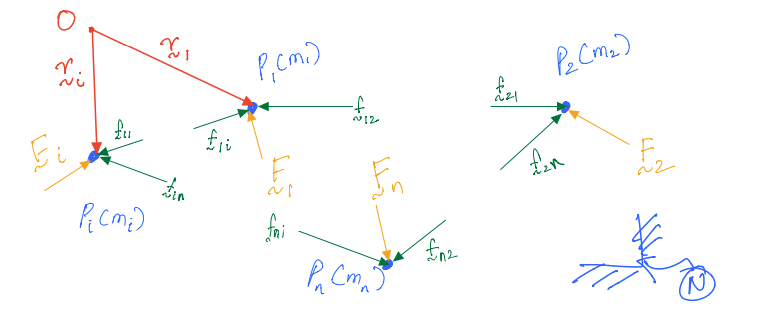

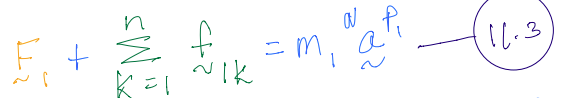

Consider a system of n particles and an inertial frame \(N\). Each particle experiences an external resultant force and a set of internal forces. The internal forces are reaction forces applied by each particle on all other particles within the boundary.

So far, everything we have studied addresses the kinetics of a point mass; the point mass was either a particle (e.g., a satellite) or a mass centre of a system of particles. This only describes the translational motion or the translational dynamics, which is based on Newton’s second law (the time derivative of linear momentum is equal to forces acting on a system). So what about the rotational dynamics?

Rotational dynamics¶

Much like how the translational dynamics inherently makes use of the concepts of linear momentum and forces, the rotational dynamics can be studied by making use of angular momentum (moment of linear momentum) and moments of forces.

We will derive the relevant equations by again making use of the system of particles from before (also shown in figure below). We also introduce a point \(O\) as we know that the concept of a moment of a vector is defined relative to some point in space.

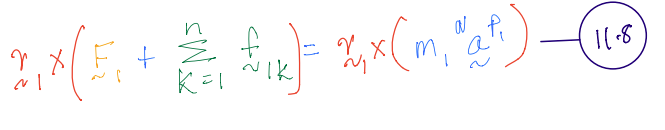

We now begin by considering the equation of translational motion for \(P_1\):

We can cross multiply it on both the right and left sides by \(\vec{r}_1\), the position vector from \(O\) to \(P_1\):

In essence, what we have done is taken the moment about point O of vectors on the right hand side and left hand side.

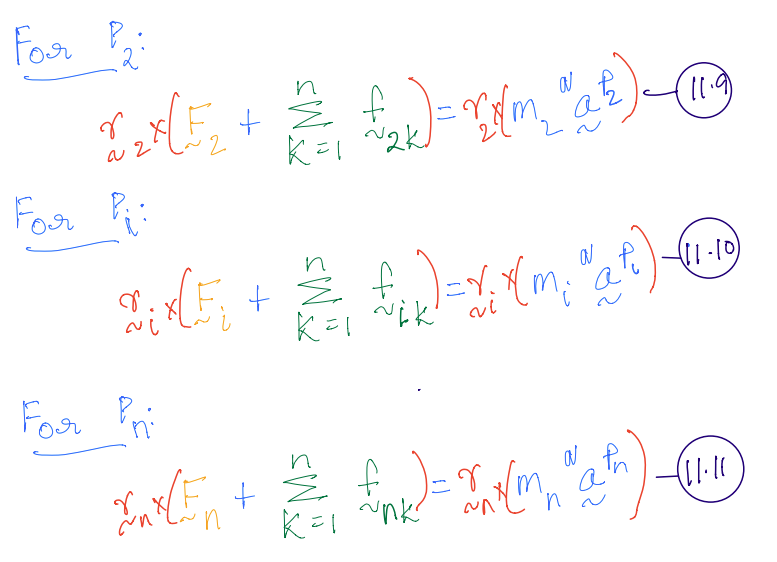

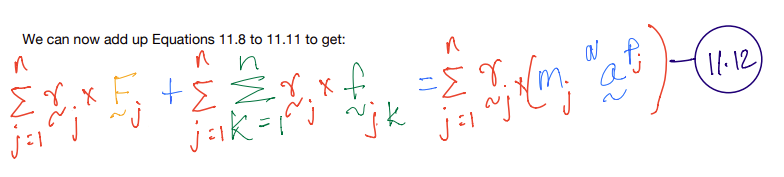

We can repeat these for the other particles \(P_2, \ldots, P_i, \ldots, P_n\) in other words, we can take the moment about point O of their translational equations which were given by equations \(11.4, 11.5\) and \(11.6\).

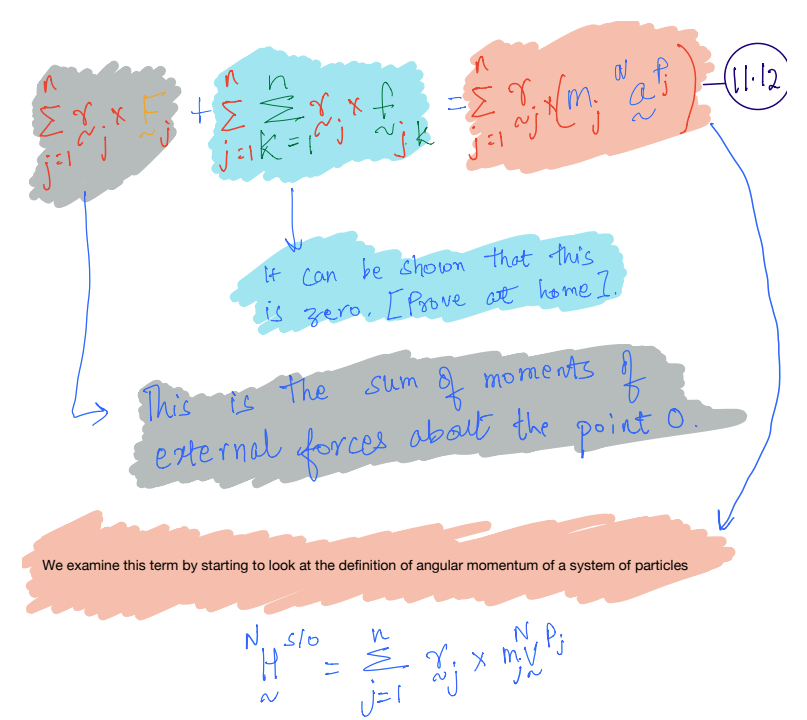

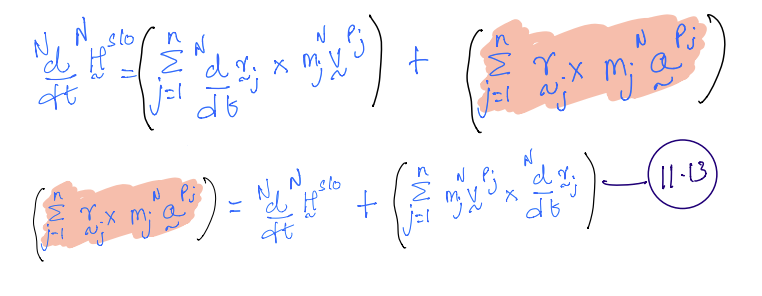

Let’s examine each term of \(11.12\):

So, the time derivative of this system’s angular momentum vector taken from the inertial frame N is

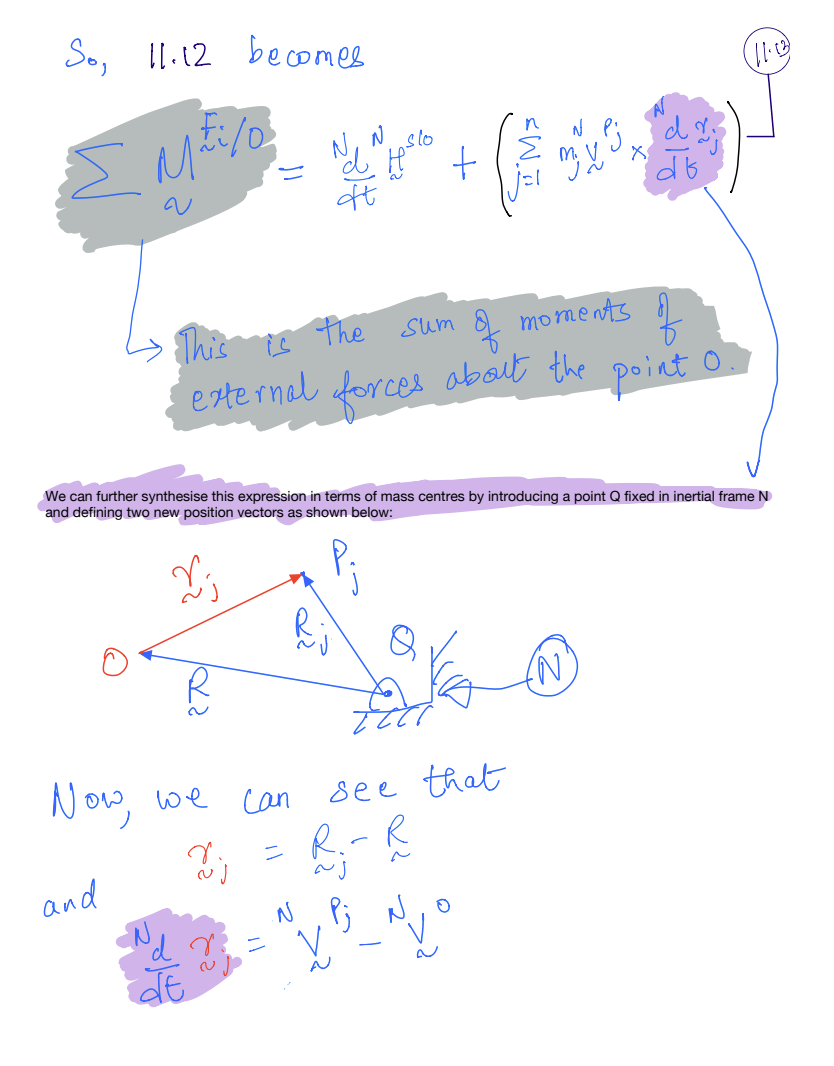

So, \(11.13\) can now be rewritten finally in a much simpler form as:

We began by examining the equations of motion of a single particle \(P\) by Newton’s second law:

Then, we looked at a system of two particles and used that as a stepping stone towards deriving a generalised Newton’s second law for a system of any number of particles. This resulted in:

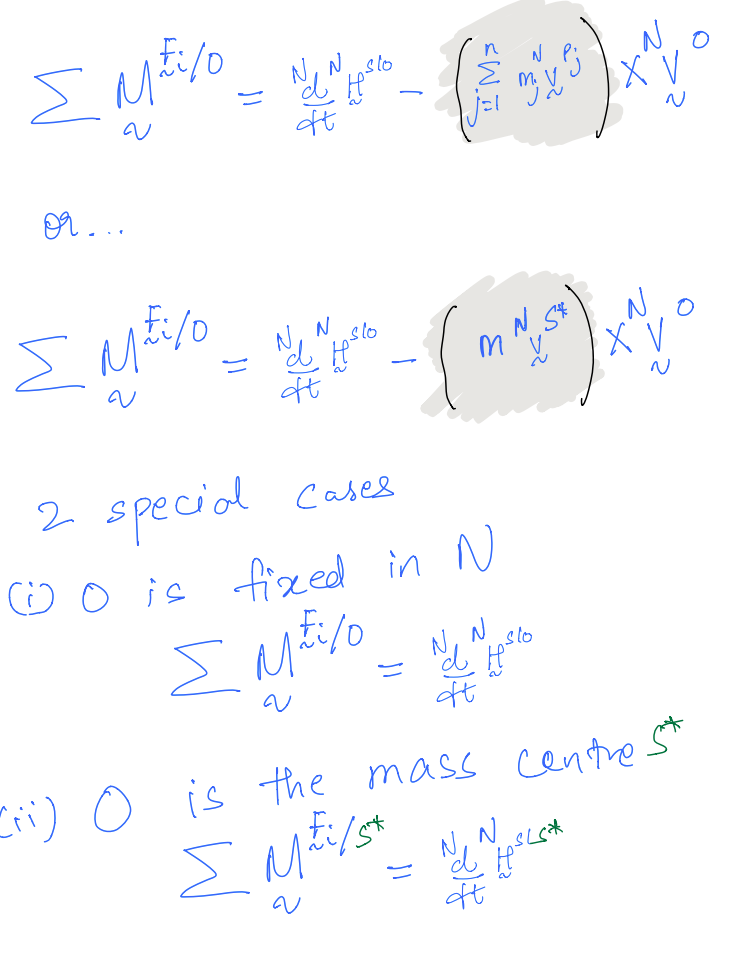

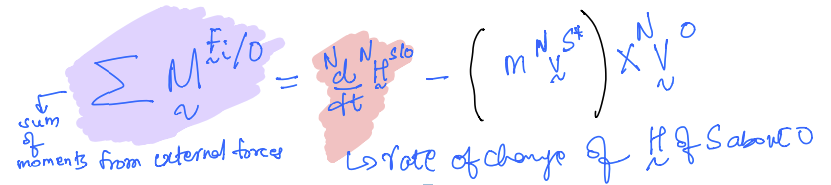

We then used the generalized Newton’s second law to derive the rotational dynamics of the system relative to a frame \(N\) by taking the moment of the translational motion about some arbitrary point \(O\). The equations for rotational motion were then found to be:

As this rotational equation was derived from the generalized Newton’s law, this result is also general. By that, we mean that this is for general \(3D\) rotational motion of a system of particles (\(S\)) relative to an inertial frame \(N\). So, this can quite easily be used to study a more specific kind of planar motion (e.g., rotation about a fixed axis and general plane motion) can be studied by starting from this general set of equations and appropriate analysis of our given problem.

Lastly, we saw that the above equation simplifies when the point \(O\) is either:

case 1: the mass centre; and/or

case 2: a point that is fixed in

In both cases, the last term involving cross products on the RHS of the rotational equation drop out.

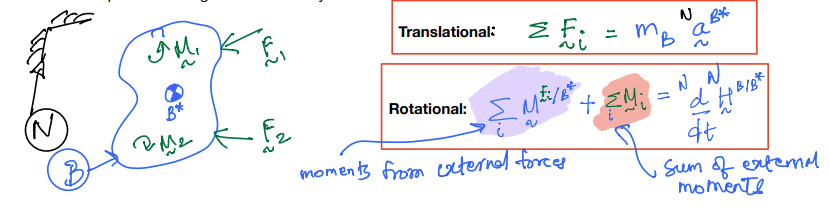

Translational and Rotational Kinetics of a Rigid Body¶

Important

The generalized equations of translational and rotational motion that have been stated above for a

system of particles are equally valid for the rigid body; shown below is a rigid body \(B\) in general \(3D\) rotation (see

Lecture 4 rigid body kinematics_ orientations.pdf for classification of types of motion). The equations of motion

are also provided alongside for this body.

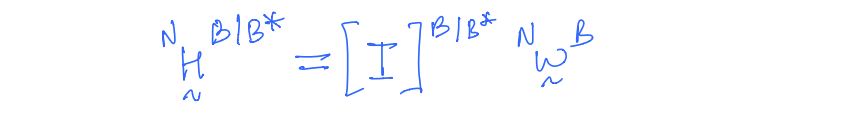

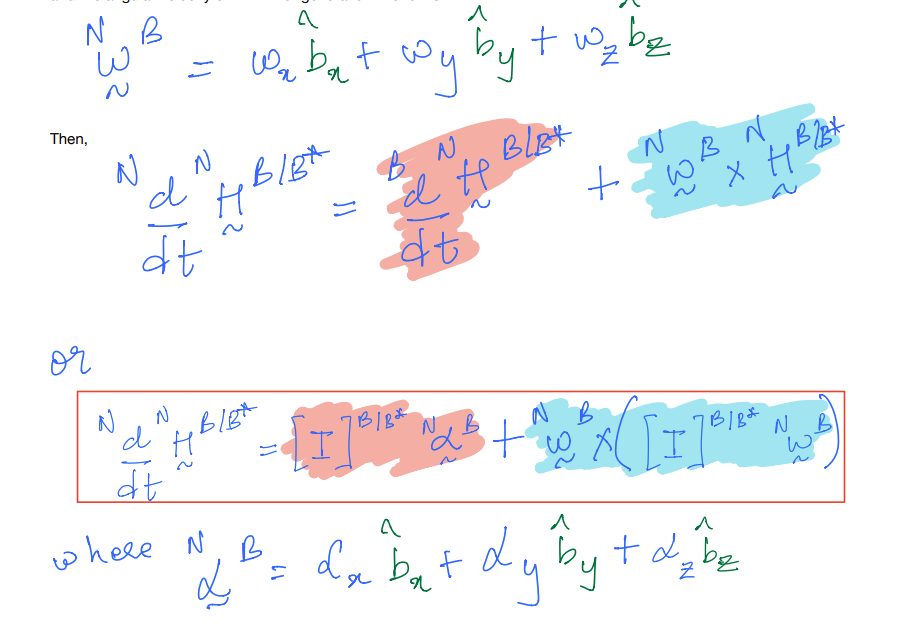

Let’s briefly examine the rotational equation further. Now, we know that:

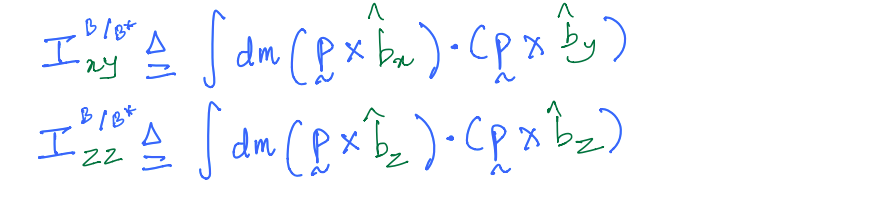

Now if the inertia scalars of \(B\) about \(B^*\) are defined in the \(B\) frame; for example:

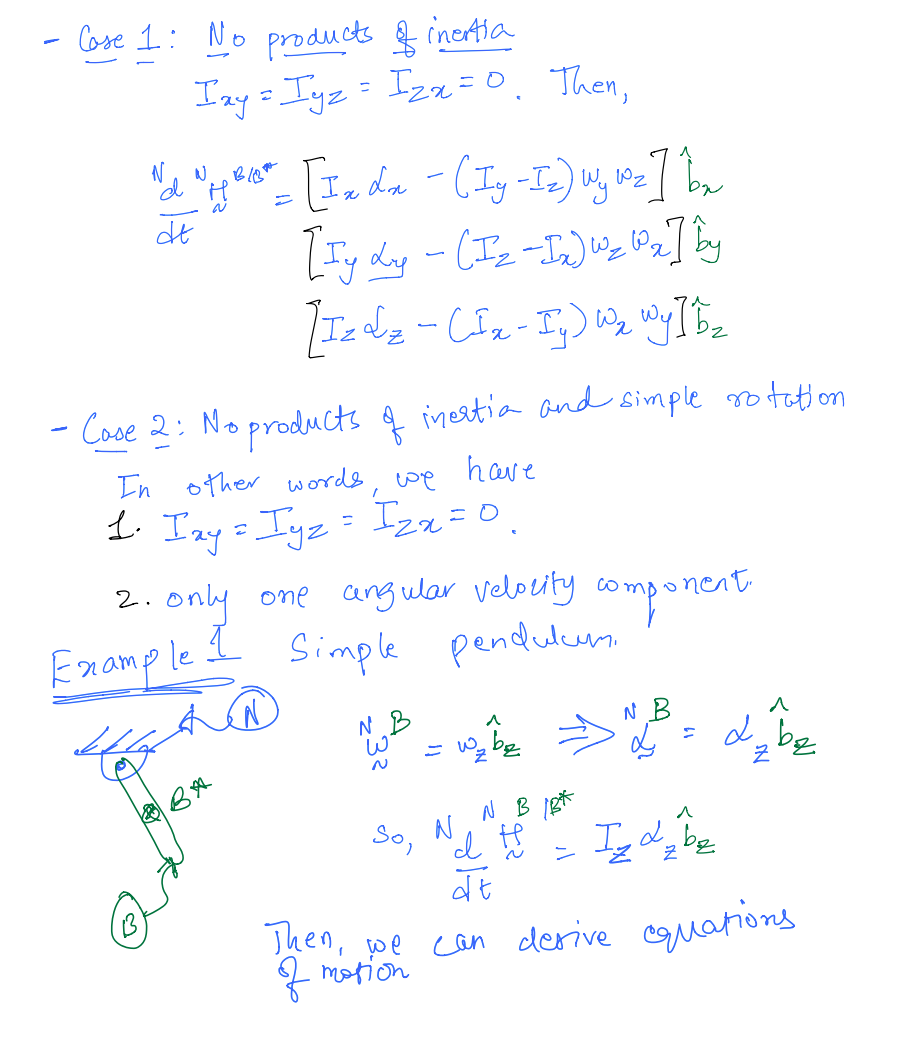

So, now we can look at what happens to the scalar equations of motion in each of the directions. We do so for two cases:

Example 2:

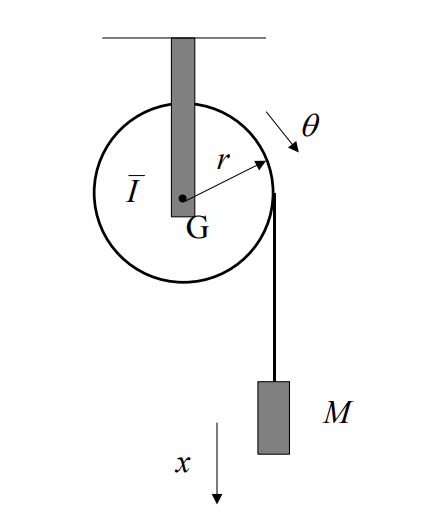

The system shown in the figure above consists of a pulley constrained to rotate about its centre of mass \(G\). A light cord is wrapped around the pulley and the free end is attached to a mass of \(10\;kg\). The radius of the pulley is \(0.15\;m\) and its moment of inertia about \(G\) is \(0.4\;kgm^2\).

If the mass is released from rest what will be its velocity after one revolution of the pulley.

With reference to the free body diagram above, the pulley is constrained to rotate about its centre of mass, \(G\). Therefore the only equation of motion of importance is the balance of moments about the pulleys centre of mass as follows:

Therefore,

And for the mass, motion is in the x-direction only with no rotation.

Finally, from geometry,

Therefore,

And

Hence we have three equations and three unknowns, \(T\), \(\ddot{x}\) and \(\ddot{\theta}\).

Eliminating \(T\) and \(\ddot{\theta}\) leaves:

After one revolution, the mass will have traveled a distance, \(s = 2\times S \times 0.15 = 0.942\;m\). For constant acceleration and zero initial velocity,